Becoming Understood

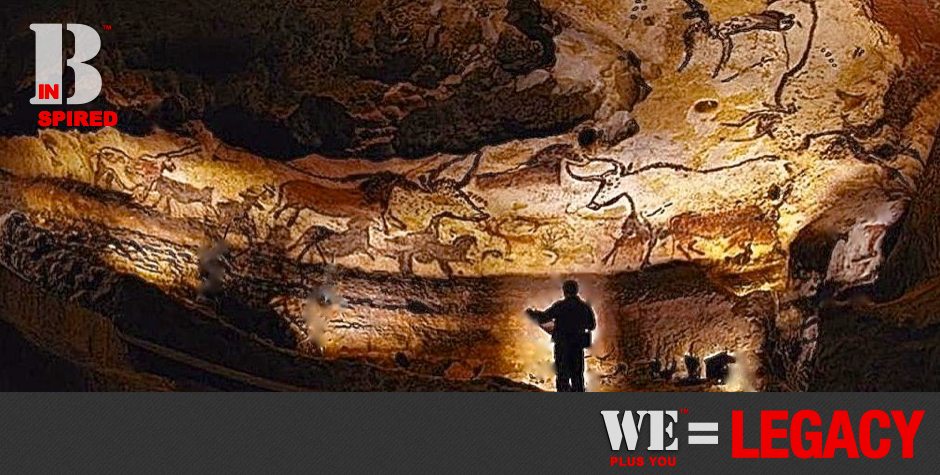

Looking Back

Looking Back

Excerpt from a speech given by National Geographic Society anthropologist Wade Davis, at TED Talks 2008.

All of humanity, probably, is descended from a thousand people who left Africa roughly 70,000 years ago. But the corollary of that is that we are all brothers and sisters and share the same genetic material. All human populations share the same raw genius, the same intellectual acuity. And so whether that genius is placed into…technological wizardry…or by contrast, into unraveling the complex threads of memory inherent in a myth, is simply a matter of choice and cultural orientation.

There is no progression of affairs in human experience. There is no trajectory of progress. There is no pyramid that conveniently places Victorian England at the apex and descends down the flanks to the so-called primitives of the world. All peoples are simply cultural options, different visions of life itself.

Right now, as we sit here in this room, of those 6,000 languages spoken the day you were born, fully half aren’t being taught to children. So you’re living through a time when virtually half of humanity’s intellectual, social, and spiritual legacy is being allowed to slip away. This does not have to happen. These people are not failed attempts at being modern — quaint and colorful and destined to fade away as if by natural law.

In every case, these are dynamic, living peoples being driven out of existence by identifiable forces. That’s actually an optimistic observation, because it suggests that if human beings are agents of cultural destruction, we can also be the facilitators of cultural survival.

The Importance of Community

Just as everyone needs love and friendship and an opportunity to contribute to the lives of others, everyone needs community. We all need to know and believe that we are a part of something bigger than ourselves. Whether they are comprised of our family, a community of friends at work, church or the gym, our social groups are sources of comfort in our lives and are beneficial to our health.

The Importance of Everyone

No matter who you are or what you’ve been told, you are important. You have something unique to contribute to the greater society in which you live. You have a talent, a skill, an interesting insight or a story to share. Just by accessing and giving that asset to a community, you bring a unique and necessary perspective to the social conversation, one based on your individual experiences: how you’ve gotten around and interacted with the world, what you’ve been taught and how you’ve been treated.

Being “In” Versus Being “Of” the Community

What if a person is not given the opportunity to participate fully in his community, and to contribute to its greater good? Though anyone can be “in” a community, it doesn’t always follow that he or she is considered “of” the community. In order to truly be “of” a community, a person must secure the status of “member” as bestowed by a person or majority group within the community.

A community member must be recognized, validated and supported by law makers, educators, employers, public and social service, housing, and medical providers, by the various religious communities and by the general population. In receiving anything short of that broad acceptance, a person remains marginalized: “in” but not “of” community, and lacking a sense of equity. Without equity, without voice, and without opportunities to participate in a community, a person risks being unnoticed, unfulfilled, and marginalized.

The Struggle Against Marginalization and the Desire for Belonging

A National Organization on Disability/Harris Survey indicates that people with disabilities feel more isolated from their communities, participate in fewer community activities, and are less satisfied with their community participation than are citizens without disabilities. Loneliness, and the isolation propagated by it, has been proven, through many studies, to contribute to sickness and even death.

Access to others, to a community, has been an elusive dream for many people with disabilities, especially for those with significant physical and cognitive differences. For as long as records have been kept, people living with disabilities have been regarded and treated as “different”.

Like many marginalized groups of people, they have been feared, separated, isolated, mistreated, ridiculed, put on display and exploited, denied medical treatment, even killed simply for their differences. Too often, citizens with disabilities are quickly discounted, unfairly dismissed as having nothing to bring to the community table. This instinctive dismissal is the result of a paradigm of low expectation that is based upon old or misguided information and is deeply entrenched in our community psyche—a psyche that equates “disability” with “inability”.

This is just one example of the subconscious assumptions that the general public make about people with disabilities. Such assumptions are especially common among people who have no real world, hands-on experience with people with disabilities. The way people think, especially those with no “real, hands on” experience with people living with disabilities. Because of this pervasive societal mindset, people living with disabilities are often viewed as “less than” others, “less deserving” of equity, or of having a voice. Nothing could be further from the truth.

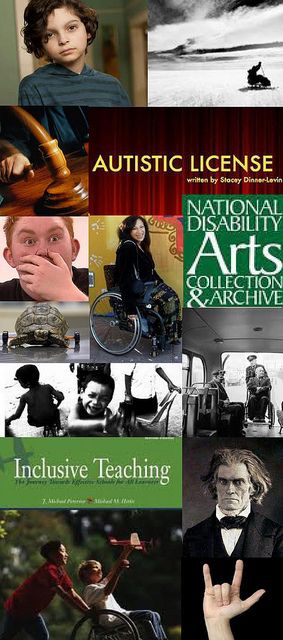

A History of Contribution

Throughout history, countless societal contributions have been made by people living with disabilities. By omitting this element of history from our studies, we’ve unknowingly perpetuated a myth of non-contribution. Though many of us grew up studying important figures like Abraham Lincoln and Winston Churchhill, Claude Monet and Henry Matisse, Thomas Edison and Albert Einstein, we likely spent little, if any, time, discussing the impact their disabilities had on shaping their lives and influencing their contributions.

At It’s Our Story we believe it likely that, for each of these figures, the perspective on life gifted them by their disabilities helped set them apart, helped impel them to write the way they wrote, paint the way they painted, compose the way they composed, lead the way they led.

Where would we be without the unique insights of Homer or Socrates, without Keats, Milton or Shelley, without Mozart or Beethoven, or Newton or Franklin? Imagine a world that never included a Stephen Hawking or St. Paul, Ray Charles, Stevie Wonder or Andrea Bocelli.

Millions of people are currently living with disabilities, with gifts and talents to share if only we, as a society, as a community, chose to open our eyes and minds.

Where We Are Now?

This is not to suggest that there has never been any positive change in general perceptions of people with disabilities. Today people with disabilities benefit from more and better access to venues: more automatic doors, smoother access routes from parking options to building entrances, and more attention paid to mobility and usability in stores. There have also been considerable improvements in transportation: kneeling buses, accessible train cars, and more aware and better trained support staff at airports have made the lives of many people with disabilities a little bit easier.

Inclusion in the field of education is also improving, but undoubtedly has a long way yet to go. Employment for people with disabilities is also still dismal. In a time at which America is feeling the effects of an unemployment rate hovering around 10%, unemployment for adults with disabilities floats in the high 40th percentile. With 70 million baby boomers now reaching their late fifties, employment for people with disabilities should be at the forefront of the public mind in America.

Improvements in accessibility, whether at the social level or in housing design or elsewhere, don’t just benefit people with disabilities—they benefit everyone. Everyone uses curb-cuts, automatic doors and ramps. Better access to and throughout a community creates more opportunity for interaction among all of its members. More opportunities for interaction lead to better understanding and less fear. Many people are already coming to see that living with disability is not a bad thing, it’s just a different thing. Such a shift in attitude and awareness allow us an opportunity to move forward toward a more inclusive community.

Where We Are Going?

Despite our societal progress, studies continue to show that people with disabilities, more than any other minority group, often remain isolated and set apart from larger communities (A. Condeluci, Cultural Shifting, 2002). In most cases, however, this isolation is not due to it is not the person’s disability itself, but instead to lack of community acceptance and a persistence of negative attitudes toward disability among human service professionals, community recreation professionals and employers.

A Social Reality Check

Studies show that the average person without a disability can count around 150 people as members of his or her various social circles—a number that falls in line with British anthropologist, Robin Dunbar’s “Rule of 150″, which speaks to the capacity of the human brain to formulate and maintain relationships. For individuals living with significant disabilities, however, studies show that social circles include only about 15 people.

This number, merely 10% of the norm, accentuates the problems created by communities that fail to provide natural and equitable opportunities for people with disabilities. Sadly, many people with pronounced disabilities report their closest “friends” are those people in their lives who provide them with daily support—in essence, those “paid” to be there.

In an effort to build more inclusive, understanding communities, It’s Our Story works to build community partnerships with disability organizations while educating young people in new media skills and aiming to create a more accessible, inclusive world.

A Call to Action

Any attempt to change attitudes and create more inclusive digital economies is a tall order. IOS is dedicated to this challenge and is proud to meet it head-on. If you would like to know more about our work—or, if you would like to help us at an individual or organizational level, please . . .